|

New York News Publishers Association |

|||

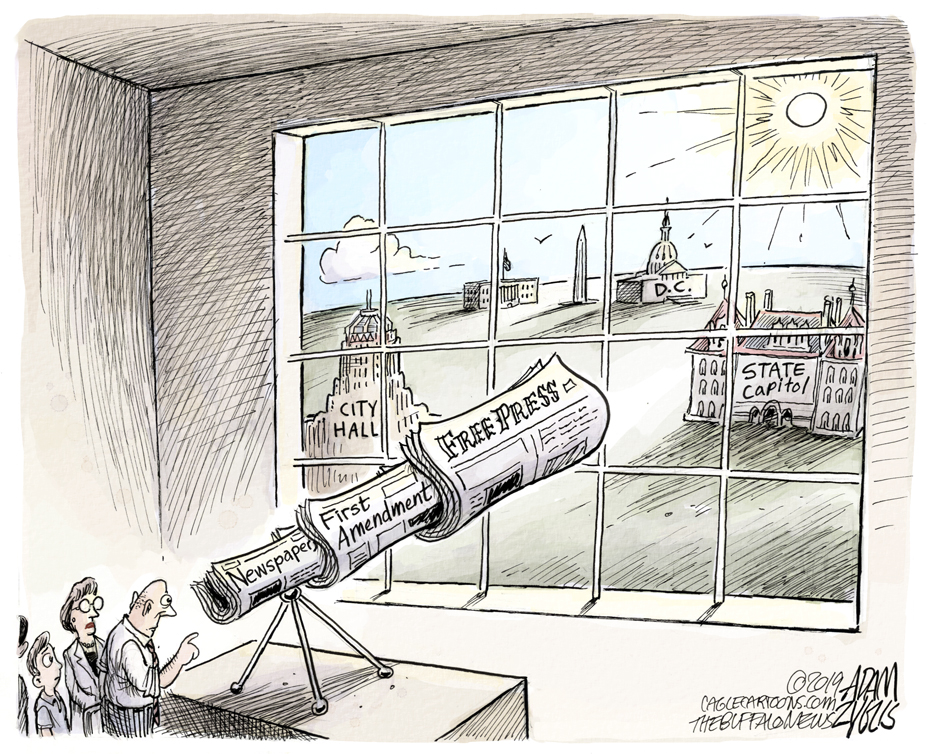

Sunshine Week 2019 - March 10-16

Sunshine Week is a national initiative to promote dialogue about the importance of open government and freedom of information. Participants include news media, civic groups, libraries, nonprofits, schools and all others interested in the public’s right to know. Sunshine Week seeks to enlighten and empower people to play an active role in their government at all levels, and to give them access to information that makes their lives better and their communities stronger.

Click here to access a set teaching resources including graphic organizers highlighting Freedom of Information & Sunshine Week.

Below you'll find commentary and editorials about the importance of Freedom of Information. This content is available for all NYNPA member publications to reprint with attribution to increase public awareness of Sunshine Week and their right to know. Additional content will be added as it is received.

Committee on Open Government Department of State

|

Freedom of Information Laws - Pushing v. PullingSweden’s Freedom of the Press Act is generally cited as the world’s first law granting rights of access to government records to the public. The phrase “freedom of information” (FOI) did not become widely known or used until passage of the United States federal Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) in 1966. The federal Act was weak and completely revised in 1974 on the heels of the Watergate scandal. Its enactment opened the floodgates, and within 10 years, every state in the US had enacted some sort of access to records law. As a concept, FOI has become international. Today there are approximately 100 nations that have enacted an access to information law, and many have jumped ahead of the laws in the US. When I’m asked, “which state has the best freedom of information law”, my answer is “Mexico”. Mexico? I started discussing FOI with Mexicans around the turn of the last century, when it was predicted that 75 years of one party rule would come to a close. That happened, and reform minded Mexicans passed a remarkable FOI law in 2002. And they did what we couldn’t have done when our laws in the US were passed in the ‘70’s - - they built information technology into their law. Think about the ‘70’s - - high tech was an electric typewriter and we used carbon paper to make copies. There was no internet or email. Mexico’s was the first law that gave people the right to request and obtain records by using email. We learned from its experience, and New York was the first state to include the right to seek and obtain records via email in a provision enacted in 2006. The Mexican law also requires “proactive” disclosure: posting records of significance on a website even before anyone requests them. That makes life easy for everyone. People can obtain records any time of the day or night, and often they can acquire the equivalent of a thick report quickly, easily and at no cost. Government staff need not respond to a FOI request if the records are accessible online. Everybody wins. And what happens when the government concludes that certain records are frequently requested and clearly public? They post them online. They “push” the records out to the public. Historically in this country, our FOI laws are based on the right to request government records, to “pull” them out. In other nations, the emphasis is to “push” them out. More and more here, government agencies are posting records on their websites, pushing them out to the public. The public today can often gain access to information readily that would have been difficult if not impossible to obtain not so many years ago. That’s great. We must think, however, about issues associated with government’s inclinations when it pushes information out to the public online. Very simply, government pushes out what it wants us to know. It likely doesn’t push out what it doesn’t want us to know. The trend toward pushing out information is the way of the world, and it will be with us forever. We’re addicted to gaining access to information from one screen or another. That’s fine, but only if we continue to have the right, a right guaranteed by law, to pull out the information, especially the information that government doesn’t want us to know. That’s why we need strong FOI laws in New York and throughout the nation. As Judge Louis Brandeis suggested more than a century ago, “sunlight is the best disinfectant.” |

By Seriah Sargenton, David Meister and Caroline Aurigemma For The Daily Gazette, Schenectady

|

Student journalists fight for lightAccess to information and public records is crucial in order for student journalists to serve the public and share information that may otherwise not be accessible for professional journalists in the field. Student journalists learn by going out and reporting in the field. We try to practice the same professional strategies the professionals use. When we use the Freedom of Information Law, we too are pulling back the dark curtain that sometimes shields information from the public. In training to produce professional journalism, students are sent to gather information by interviewing government officials and using the Freedom of Information Law to acquire public records about various subjects. When we make efforts to collect information for stories, government officials sometimes don’t offer us the same courtesies they do to professional journalists. We compete with local news organizations to scoop news and features. Sources tend to categorize student journalists as unprofessional, untrained, or unsure of what we are doing in the field. This mindset contributes to sources often stalling our efforts to get to the truth. Transparency between sources and the reporter is important for various reasons. We are trained to conduct interviews with a central focus and ask many questions, but most of all, listen to our subjects. Students conduct intense research prior to their interviews. However, our path to reporting stories is often thwarted before the research or interview has begun. Student journalists provide a public service to their communities when writing about neighborhood issues. When elected officials are transparent and forthright with student journalists, they’re demonstrating the behaviors that landed them in office. According to the Open Meetings Law, minutes and agendas are to be available to the public one week after the executive session. When representatives of local governments obstruct access to information or resist simple requests for public documents, they are violating the spirit of our open records laws. Students reporters impact the local media. Last month, an Alabama newspaper printed an editorial calling for the return of the KKK, and that event became national news. How? Student journalists took a photo of the editorial and away it went. We regularly use Freedom of Information Law (FOIL) requests to obtain records from government outlets ranging from the state Department of Corrections and Community Supervision to the city’s fire department reports. Document-based journalism is something we are taught from day one. It’s the toughest kind of reporting, but the results and effects of the final publication are rewarding, and it can lead to real change. When a government agency like the Corrections Department makes information available online, student journalists and the public benefit from access to that information. When reporters at Saint Rose updated a story about a hit-and-run crash involving a student who died, access to the state’s database enabled those students to update the story for their community of readers. No other local news outlets reported that fact. That’s why Freedom of Information and Open Meetings laws are so critical, as they allow not just journalists, but the public as well, to see what elected officials are doing, especially when it comes to spending taxpayer dollars. Seriah Sargenton is a senior at The College of Saint Rose in Albany studying communications with a minor in creative writing. She is the assistant editor of The Chronicle, the college newspaper. David Meister is a junior from East Greenbush studying broadcast journalism. He is the sports editor of The Chronicle and vice president of Saint Rose Television. Caroline Aurigemma is a senior studying communications at St. Rose. She is the copy editor and photography editor of The Chronicle and president of Saint Rose Radio Club. All are students in Dr. Cailin Brown’s advanced journalism class. |

Editorial Page Editor

|

Uphill battle for transparency in government continuesTry this tonight on the way home. If you see a police officer camped out by an intersection, run the stop sign. When the officer pulls you over, explain to him that you only choose to obey certain traffic rules, and that stopping for stop signs isn’t one of them. Think he’ll agree with you and not give you a ticket? OK, don’t really run a stop sign. We’re just making a point here. The point is that laws are passed for a reason and they were meant to be obeyed. People don’t get to decide which ones they’ll follow and which ones they won’t. Yet despite actual laws ensuring the public’s right to learn about their government through access to public records and public meetings, government officials still regularly decide not to follow them. This week, we in the journalism profession celebrate Sunshine Week to focus the public’s attention on government transparency. What would really improve transparency in government is if the government agencies just follow the existing laws. In many cases, they know they’re violating the law and choose to deliberately blow through legal stop signs. Other times, they claim ignorance of the law in refusing to comply with it. And in other cases where the language of the law is ambiguous but the intent clear, they err on the side of secrecy. Almost every day, journalists and citizens encounter public officials who routinely deny access to records without trying to comply with the law, who refuse to follow established deadlines for notification and compliance, who close public meetings illegally by citing phony exemptions or lying about the reason for closing the meeting. Citizens routinely have to fight for basic public documents like police reports and mugshots and budget information. For example, The Gazette and other media outlets recently sought information about safety issues related to the intersection of October’s fatal Schoharie limousine crash. Officials hid behind subjective language in the law that allows information to be withheld if it was compiled for law enforcement purposes. They also withheld statistical information in defiance of the language and spirit of the law. One of our reporters recently tried to obtain a salary schedule for a local municipal water authority and was told the agency had payroll records, but not job titles. They have to have a list of compensation for each position somewhere. But instead of releasing the information, they’re giving us, and their constituents, the runaround. In October, the Albany Times Union was denied access to emails between state Health Department staff and a major donor to Gov. Andrew Cuomo. Not only would the department not turn over the records, officials wouldn’t even explain why the department couldn’t conduct a search of its own computer system that was the basis for its denial. For two years, the Buffalo News sought a videotape showing a cell block attendant abusing a criminal suspect in the basement the City Court building.Here we have a government employee in a government building committing some kind of act against a citizen, yet government officials felt they had the right to keep the tape secret from the public for two years. The Post-Star in Glens Falls has for years published local deeds, along with the sale prices of the properties. That is until recently, when Saratoga County arbitrarily decided to remove the sale prices from the listings. Only after calling out the county on its pages and consulting with industry and state officials did the paper convince the county to restore the sale prices. This defiance of open government laws isn’t limited to state and local governments. On the federal level, the Trump Administration is so secretive that good-government groups have dubbed its record on transparency “an eclipse” on sunlight. To be fair, the Obama and Bush administrations also had awful track records when it came to withholding records and not releasing them in a timely manner. Unfortunately, the disturbing pattern toward greater secrecy continues. We could go on all day with examples of how government regularly abuses, ignores, obfuscates and violates existing transparency laws, with the ultimate outcome being the public is deprived of information about government to which they are rightly entitled. We must say that not all public officials behave this way. To those officials who do follow and respect the law, thank you for your integrity and cooperation. If any progress can be made as a result of this year’s Sunshine Week, let it be that more public officials respect the people’s right to know and recognize and reject efforts to deny citizens that right. |

Journalists may make politicians antsy, but that’s necessary in a democracyThere’s no disputing it: The press can be a pain in the neck to public officials. Reporters watch them, question them, challenge them, periodically anger them. Sometimes, their work puts politicians in the cross hairs of prosecutors. It’s part of the job description, one that the Founding Fathers saw as crucial to the success of a democracy. Thomas Jefferson, who sometimes detested the press, put it this way: “The only security of all is in a free press.” That’s a far cry from being the “enemy of the people.” All people do things they wouldn’t want printed in the newspaper, of course. We are, all of us, only human. But when public officials act in ways that compromise their offices, the public has an interest. It is the job of reporters to tell those stories – straightforwardly, fairly and without fear of the repercussions. That is worth celebrating at the start Sunshine Week, an annual celebration of public access to public information. Not all public officials are on board. Take Chris Collins. The Clarence Republican pronounced The Buffalo News to be smearing him with “fake news” as it pursued the story of how his congressional position intersected with his business interests in Innate Immunotheraputics. He now stands charged with federal felonies related to insider trading. It was real news, all along. Real news is all around and it can be uncomfortable for its subjects. The mismanagement of the Erie County Water Authority and the Buffalo Municipal Housing Authority are real. The crisis in Erie County jails is real. They all take money from taxpayers’ pockets. The Buffalo News told its readers about all of that. The paper has also informed Western New Yorkers about the abysmal treatment of many nursing home residents here. It exposed the disturbing extent of the sexual abuse of children by priests and the Catholic Church’s role in covering it up. Real and real. The News revealed that an Erie County sheriff’s deputy, Kenneth Achtyl, had attacked a fan at a Buffalo Bills game, breaking his nose, and mistreated a woman leaving Chestnut Ridge Park. Just in the past several days, it has reported on suspicious activities at the Community Action Organization of Western New York, which spends millions of public dollars. Nothing fake there. It’s not just The Buffalo News, of course. It was real when The New York Times pursued the Whitewater story early in President Clinton’s first term. It was real when the media reported on Monica Lewinsky’s blue dress. Iran-Contra was real. Watergate was real. The official lying about the Vietnam War was real. Abu Ghraib was real. It’s no secret that President Trump doesn’t much like the news media. In that, he has plenty of company among his predecessors. But it counts as a sorrowful and dangerous escalation when he smears journalists as the “enemy of the people.” With that divisive tactic, the president of the United States undermines the First Amendment, which he swore to uphold as part of his oath. What is more, the claim is transparently false. Robert Mueller’s investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 election has led to charges or convictions of at least 34 people and three companies. Several were directly associated either with the Trump administration or the campaign. It may be disturbing to the president that journalists are digging into this, but it doesn’t make them the enemy of the people. Just the opposite. What they are reporting is real. Journalists make mistakes. When they do, it’s also their job to correct them, promptly and forthrightly. But a mistake, on its own, isn’t proof of ill-intent. It’s simply evidence of the human fallibility of men and women doing important work. And that’s the point. Journalists from The Buffalo News to the nation’s biggest dailies, and from local television to the national networks, are professionals committed to a job appropriately ensconced in the Constitution – one that they will continue to do, as best as they can. Straightforwardly, fairly and without fear. |

Jolene Cleaver |

Sunshine Week spotlights local, statewide freedom of informationIn January 2018, the activist group #NoHospitalDowntown began circulating hundreds of emails from various local officials related to the planned downtown Utica hospital. The emails, obtained in response to a Freedom of Information request, made headlines as they offered a glimpse into some of the behind-the-scenes conversations that may have helped shape the project. In November, the Observer-Dispatch used a Freedom of Information request to obtain a notice of claim filed against the city of Utica by former Valley View Golf Course manager Gary Madia, who was claiming wrongful termination. These are just two examples of how journalists and private citizens alike can use state and federal Freedom of Information laws to access records held by the government — and the kind of information that can be learned as a result. Today is the first day of Sunshine Week, an annual initiative organized by the American Society of News Editors to promote dialogue about the importance of open government and the federal Freedom of Information Act, also known as FOIA. In New York, government records also are covered by the state’s Freedom of Information Law (FOIL). The public’s right to access government records has the potential to make their lives better and their communities stronger, according to the American Society of News Editors. Brett Orzechowski, an assistant professor of management and media at Utica College, teaches a watchdog class at the school about data gathering. He said one of the tools students learn for their toolbox is using FOIL and how information gathering is used in the business and governmental spheres. “All this public data comes from somewhere,” he said. But when it comes to accessing particular public records, “a lot of people don’t know they can access it,” Orzechowski said. What’s available? In New York, all records held by state agencies are considered public unless they are specifically exempted under the state’s Freedom of Information Law.

Procedures exist for an appeal if a request is denied. “Given the sensitivity of law enforcement records, including the privacy interests of those involved, especially victims, some records may not be available to the public,” New York State Police spokesman William Duffy said in an email. “Every request is reviewed thoroughly before a determination is made to withhold any records.” Handling requests Along with traditional mail and fax as available, most agencies now also accept requests through email or through online forms available on their websites. The New York State Police received 3,250 FOIL requests in 2018, Duffy said, though troopers are expecting to surpass that number this year. He said most of the requests concern incident and investigation reports. Meanwhile, the requests fielded by local governments are much more varied. “All types of various information (is requested),” Pulverenti said, “From codes to police to fire to engineering to finance ....” In Oneida County, County Clerk Sandra DePerno said she handled 87 records requests last year. This year, she had filled 15 requests as of Thursday. County residents can submit requests using a downloadable form available from the county website. Those requests are reviewed by a county attorney before they are relayed to DePerno. Most requests, she said, come from private citizens who want to know more about government actions. “I pull records for anything they need,” she said. “It all comes through my office.” “They are typically for things relative to properties. Like people looking for property history,” Seelig said. Herkimer County Attorney Rob Malone said the county received about 85 records requests in 2018, noting the county receives requests from “all over the place from local and national entities.” “It keeps us busy,” he said. Enforcing the rules Executive Director Robert Freeman often is called upon to give advisory opinions on whether certain information is or isn’t public under Freedom of Information Law. He also travels the state and conducts 75 to 80 public presentations each year on FOIL and open government. For those presentations, which include question-and-answer periods with community members, Freeman prefers to go in without an agenda and let them guide the conversation, he said. “I don’t know what’s bothering a community,” he said. “In Utica, it might be a downtown hospital. ... It’s different everywhere.” Typically, questions center on land use and public money issues. Many can be answered with a little research, either through an official FOIL request or an online search. “Governments in the United States put a lot of information online,” he said. People just have to know how to access what isn’t there. FOIL’s future As New York goes through its budget process this year, for example, there are a few proposed public information changes that may be considered. General Government Article VII, which includes a provision that would shield law enforcement agencies from publicly disclosing the identity of persons who have been arrested. If enacted as part of the state budget, it would add booking information and mug shots to the list of information for which disclosure is considered an unwarranted invasion of personal privacy. As of Thursday, that measure still was working through finance and ways and means committees. As public thought on the freedom of information is ever-evolving, Orzechowski predicts the balance of public versus private information will continue to be debated against the backdrop of the public’s, “right to know.” And while this is going on, Orzechowski and Freeman both noted that state and local governments are continually looking for ways to provide more government records online. The push for open data is something we will be hearing more about,” Orzechowski said. |

Editorial Board of

|

Sunshine Week is for all of usFor this week, The Citizen's opinion page will be featuring commentary related to the open importance of government transparency. It's one way we try to bring attention to the advocacy and public education campaign known as Sunshine Week. Journalism organizations are involved in organizing Sunshine Week promotions and events, and news media are always among the most vocal participants in this annual effort. But it's important for the public to know that Sunshine Week's chief purpose is not to talk about the value of journalism. The goal is to help the public understand that in the United States, it has the right to know what its government is doing at all levels. That concept of openness and accessibility is a foundational principle of our representative democracy. Journalists, including those who work at The Citizen, frequent use laws such as New York's Freedom of Information Law and Open Meets Law, or the federal Freedom of Information Act, to request and secure information that government officials may not necessarily want citizens to see. These efforts by the news media are ultimately made on behalf of the public, because that's a crucial role journalists play: representing the public at government meetings and court proceedings and gathering records that should be accessible to every citizen. Being that voice of the public is one of the main reasons the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution protects freedom of the press. Sunshine Week helps bring attention to this public representative role of the news media, but it also aims to help every American understand that we all have these same rights to access government information and proceedings. FOIL, FOIA and open government meetings are available to everyone. Don't let any public official tell you that only a journalist can make a record request or attend a meeting. And learn about the tools and processes at your disposal. For starters, we'll bring your attention to the website sunshineweek.org, and the account @sunshineweek on Twitter. Check out and immerse yourself in all that journalists are doing to get information you might want to see, but also ways you can get it for yourself. In New York, a terrific tool is the New York Committee on Open Government site (dos.ny.gov/coog). At the national level, check out the federal Office of Information Policy's Freedom of Information act website at foia.gov. |

|

Diane Kennedy, Executive Director New York News Publishers Association

|

Newspapers make an impact every dayAs the famous playwright Arthur Miller once said, “A newspaper, I suppose, is a nation talking to itself.” A local newspaper invites a community to have a conversation. The newspaper publishes news and opinion and provides a forum through which members of the community can share their news and opinions with one another. A local newspaper enables its charities, schools and churches to invite community members to gather together to make the community a better place. Its volunteer fire departments send in notices about the pancake breakfasts that support their rescue work, and its animal shelters send in photos of cats and dogs who need new homes. When fire destroys a family’s home or a child’s bicycle is stolen, the newspaper tells the story and its readers open their hearts and wallets. When its local government is about to sell a person’s home to pay a long-overdue tax bill, or a bank plans to foreclose on an unpaid mortgage, it is required to notify the entire community by placing a public notice in a local newspaper. Sometimes, the person’s home is saved because a neighbor or relative notifies the homeowner and the overdue bill is paid. Newspapers save their readers money, by offering local businesses a way to tell readers about sales, and helps its readers sell items by placing classified ads. Newspapers also help residents save money on their taxes. A study by the Brookings Institution and the Brandeis International Business School in July 2018 revealed that the cost of government borrowing in communities with newspapers was significantly lower than in communities without local newspapers. When there is no newspaper to keep watch over government spending and efficiency, both decline. Newspapers can also help their readers improve their own finances, through publication of advice columns on personal finance. In 2018, newspapers reported on the implications of federal tax law changes which altered the deductibility of state and local income and property taxes, directing readers to online resources to check their own payroll deductions in time to avoid surprise tax bills. Newspapers help maintain political balance and reduce the corrosive effect of political polarization, which drives a wedge of distrust between members of a community. Research by Louisiana State University, Colorado State University and Texas A&M University in 2018 showed that voters in communities with local newspapers tended to vote in a less partisan fashion, often basing their decisions on local issues and impact rather than national partisan disagreements. Newspapers offer local candidates a forum to explain policy proposals, which will then be examined by knowledgeable reporters and editors. Many of the stories the newspaper tells are controversial or upsetting to some readers, but it is often the nature of news that it is a recounting of what takes place that is out of the ordinary. Readers need to know that a beloved teacher has been arrested for abusing children, or that a government official has stolen taxpayer funds. Journalists help readers navigate the flood of information emanating from the world around them, by selecting and evaluating news of current events, filtering out information that cannot be adequately verified. Journalists are trained to view information with a skeptical eye, and to demand confirmation of its accuracy. Newspaper editors insist upon documentation to back up stories and seek out multiple sources of information whenever documentation is difficult to acquire. Journalists attend many government meetings and request government documents in order to provide their readers with vital information. Newspapers report on the criminal justice system, where judges and juries decide a local person’s freedom or safety. The simple knowledge that an impartial observer is recording events helps keep everyone honest, and that’s good for the newspaper and its community. |

Press Republican, Plattsburgh Editorial Board

|

Put teeth in Sunshine LawsNew York’s Open Meetings Law is designed to guide public officials in how they conduct their meetings and the rights of the public to attend them. The Freedom of Information Law exists to provide rights of access to government records. There’s no law, however, to enforce either. But there should be. The “aggrieved” person, according to the state’s Committee on Open Government, is free to take the offending agency to court. “When questions arise under either the Freedom of Information or the Open Meetings Law, the Committee staff can provide written or oral advice and attempt to resolve controversies in which rights may be unclear,” it says on the the Open Government website. “Since its creation in 1974, more than 24,000 written advisory opinions have been prepared by the Committee at the request of government, the public and the news media. “In addition,” it says, “hundreds of thousands of verbal opinions have been provided by telephone.” The committee can’t go further than that. Here at the Press-Republican, we know long-time committee Executive Director Bob Freeman by name, as we have consulted him many times on different matters related to the Sunshine Laws, as these directives are sometimes called. Newspapers have long been guardians of transparency in government — news stories and editorials really can shine a light on failures to comply. But newsrooms are smaller these days, which means reporters at fewer meetings. Without such a watch guard, there can develop a less stringent attention to the rules, which can then dissolve into an even more casual observance. It is generally up to the professionalism and conscience of public officials to practice transparency by following the Open Meetings Law. It is also left to their honesty to provide requested records that meet state guidelines as available through FOIL. Members of the public who attend government meetings should not hesitate to call officials to task if they believe the law is not followed. They should contact Bob Freeman’s committee, notify their daily newspaper. Public entities should be on guard against falling short when it comes to transparency, both at meetings and in providing information. They should above and beyond to prove their openness by posting agendas and minutes online in a timely fashion; the City of Plattsburgh does so, as do some other municipalities and school boards. Far too few don’t, however. In the Northern Tier, just three local governments — the villages of Rouse Point and Champlain and the Town of Champlain — have invited Home Town Cable to video proceedings, with those meetings then posted online and run on public access television. It’s a fact of life that few people attend meetings unless there’s an agenda item important to them; governments should embrace any opportunity to reach more of them. And it’s time the state puts teeth in those laws. An advisory opinion may hold water with some officials, but it’s a weak solution to the all-important transparency a Democracy demands. So, too, is leaving citizens to force accountability — few would take on the expense of a lawsuit. In some states, the state attorney general’s office is empowered to investigate complaints brought by the public. Government officials can be fined for violations. New York should follow suit. |

|

Editorial Page Editor,

|

Partly Cloudy on Sunshine WeekWhen annoying journalists like me pontificate about efforts made to conceal documents showing what our governmental bodies are up to, many people roll their eyes. It’s not difficult imagining that the typical response is, “Yeah, yeah, yeah; this makes it harder for you to do your job. Cry me a river!” People who don’t work in the news industry have their own burdens to carry, so why should they be sympathetic to the plight of my colleagues? I understand the sentiment. Few want to hear reporters and editors gripe about having to chase down specific crime statistics or the emails of public officials pertaining to policy measures under consideration. There’s so much inside baseball here that many people believe our complaints don’t relate to their lives. But having access to the information contained in public records and being able to watch governments conduct business are vital for journalists and non-journalists alike. Since municipal bodies are acting on our behalf, we all have a stake in what they’re doing. We gain a fuller picture of what these entities are undertaking by examining the documents they produce and seeing them preside over meetings. New York has an incredibly dysfunctional system when it comes to enforcing the state’s Freedom of Information and Open Meetings laws. City councils along with county, school, town and village boards far too often ignore these statutes. Why shouldn’t they? Who’s going to punish them for any violations? The only remedy for breaking these laws is legal action initiated by a private citizen or organization. Public officials or agencies may be compelled to award expenses to petitioners if courts find them guilty. However, this requires at least two things: The plaintiff must have the financial resources to file a lawsuit, and the courts need to find the defendants guilty. These aren’t easy obstacles to overcome. Violators may look for ways to prolong court proceedings; this would increase legal expenses for petitioners. And state agencies would be defended by the New York attorney general’s office, which has substantial resources to weaken rivals. Public officials are happy to delay a lawsuit as much as possible. The money to fund it isn’t coming out of their pocket — it’s being paid for by taxpayers! So with virtually no enforcement mechanism against violators, there’s little incentive for government authorities in New York to adhere to the Freedom of Information and Open Meetings laws. We often have to rely on their good faith to comply with these statutes, but this isn’t always in abundant supply. This isn’t to suggest that Albany doesn’t provide any assistance. The Committee on Open Government, operated through the Department of State, has been a vital resource. Executive Director Robert J. Freeman and members of his staff are zealous advocates for government transparency, and their advice and legal opinions have been tremendously beneficial to numerous individuals. It’s still, however, an uphill climb to persuade public authorities to follow these laws. And this doesn’t solely affect nosy reporters and editors. Local laws passed mandate what we can do with our property and where we can operate certain industries. Budgets approved determine how much money municipal governments will require. Police reports indicate where crimes are occurring and what troubling patterns are developing in specific areas. The state Freedom of Information and Open Meetings laws allow us to follow what is being done and who’s doing it. But they are largely toothless statutes designed to give the appearance of government transparency. People throughout New York should be up in arms over the fact that enforcement of these laws is so weak. But aside from some vigilant residents, persistent watchdog groups and pesky journalists, there’s not much noise. This is shameful but not surprising. Look at the dismally low voter turnout numbers in municipal elections. Why are people so apathetic about a process that has such a profound impact on their lives? We’re in the middle of Sunshine Week, which promotes the public’s right to know what public officials are doing. This annual event is organized by the American Society of News Editors and Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press. As we have throughout much of our history, we’re now engaged in very lively conversations about the future of our society. I hope these interactions are civil, although that’s not always the case. The most important thing, though, is that such discussions must be informed. And this is where the Freedom of Information and Open Meetings acts come into play. We can’t have reasonable and productive debates about how to proceed unless we possess the facts about what’s going on. Monitoring how government conducts business is everyone’s obligation. But the tools enabling us to do this, highlighted by Sunshine Week, are useless if we refuse to pick them up. |

Click here to view a video posted by the Democrat & Chronicle (Rochester) for Sunshine Week 2019.

Tax Watch Columnist Journal News,

|

Despite state law, getting public documents often faces roadblocksIn recognition of Sunshine Week, Tax Watch columnist David McKay Wilsonwrites about the ongoing roadblocks publicly funded agencies often put up in the public's quest for public information. New York's Freedom of Information Law, known as FOIL, is a journalist's best hope to access public documents to detail the inner workings of the taxpayer-financed public sector. But sometimes governments can delay the release of documents for months, with no consequences. Other government officials succeed in keeping documents secret because New York’s statute requires a legal challenge in state Supreme Court if a public agency won’t relent. Suing the government can be expensive. As part of Sunshine Week, Tax Watch has joined a national effort headed by the American Society of Newspaper Editors, which highlights the importance of open government. Sunshine Week occurs in mid-March, coinciding with James Madison‘s birthday and National Freedom of Information Day on March 16. It's a time when the First Amendment Foundation, along with hundreds of media organizations, civic groups, libraries, nonprofits, and schools, join ASNE to discuss the importance of open government. As Tax Watch columnist, I’ve run into numerous roadblocks, with my latest issues involving documents withheld in Irvington and Carmel that should be public, says Robert Freeman, executive director of the state Committee on Open Government. "Documents can be hard to come by," said ASNE's legal counsel Kevin Goldberg. "It's inherent in the DNA of people in government to hold their secrets as closely as possible. Journalists across the country have to fight for public records, all the time." Freeman said a 2017 amendment to New York's FOIL law added teeth to it by requiring judges to award attorney fees to individuals who prevailed over an agency that had no reasonable basis to deny the documents. Several plaintiffs received attorney's fees in 2018, he said. Freeman said that smaller governments tend to respond better than bigger bureaucracies, like those that run the state of New York and New York City. "The law works better as the size of the government unit diminishes," Freeman said. "There's much more direct accountability." My colleagues have run into stonewalls as well - from both big and small governments. Below are some examples of their journeys to provide you with public information. It's a dance that begins with the initial request. State law requires the documents be provided within five days. If after five days the documents can't be found, the agency has another 20 business days to produce them, at which time the agency can set a date certain when it expects to provide them. To read the complete editorial click here. |

Tax Watch Columnist Journal News,

|

Update on the editorial above: Town of Carmel reverses itself, will release report on $1M Swan Cove deal it had withheldTax Watch columinst David McKay Wilson's latest column brought action in the town of Carmel as part of The Journal News/lohud Sunshine Week campaign. A day after Tax Watch detailed how the town of Carmel was withholding a document in apparent violation of the state’s Freedom of Information Law, Carmel Supervisor Ken Schmitt said he would release it. Nevertheless, he warned that it will take several days before he makes public the title report for the town’s $1 million purchase of lakefront property in downtown Mahopac that was once owned by a partnership that included Town Board member Michael Barile. “I’ll give it to you next week,” Schmitt said. He declined to say why it would take so long. The column was written as part of the American Society of News Editors “Sunshine Week” effort, which highlights the importance of open government, and the roadblocks faced by journalists who seek documents that detail how government works. Town counsel Greg Folchetti, who had told Schmitt he would not release the report because he had it stored in his private law office, declined comment Wednesday night when asked why it would take several days to release it. Folchetti said he was not currently representing Barile or his real estate companies on legal matters. “There is nothing active that I know of,” Folchetti said. Tax Watch had sought the title report as part of its investigation of the sale, which was promoted by Barile in the fall of 2017 while he was running for Town Board. Records show his partnership, which included his daughter, Nicole, and Mahopac builder Tommy Boniello, sold the 0.6-acre parcel to Swan Cove Manor LLC for $725,000 in March, 2016. In December 2017, the town signed a contract to buy it from Swan Cove Manor LLC for $1 million. The deal was closed in March 2018. The town has withheld the document, claiming it was covered by the exemption for attorney-client privilege between the town and Folchetti. When Tax Watch appealed the denial to Schmitt, the town’s appeals officer, he said it could be kept private because town files held by Folchetti in his private law offices were beyond the reach of the Freedom of Information Law. But Robert Freeman, executive director of the state Committee on Open Government, said numerous court cases had found that documents created for the government were public, regardless of where they were stored. In an interview Wednesday afternoon, Schmitt told Tax Watch that he favored making the report public, but Folchetti insisted it be kept private. “I have no problem giving it to you,” Schmitt said. “I think it should be public. I’m not hiding anything. But Greg is saying to me that it’s in his attorney file at his office, and it’s not FOILable.” Tax Watch reminded Schmitt that Carmel taxpayers had paid for the title report, and that he was the FOIL appeals officer, whose decision Folchetti was required to abide by. Two hours later, Schmitt said the report would be released. |

|

Times Union, Albany

|

Sunshine, even for themTHE ISSUE: The Legislature continues to resist making itself subject to the state's Freedom of Information Law. THE STAKES: Why should lawmakers be exempt from transparency? What the New York Legislature wanted the public to know, it proudly informed the public of this week in a press release. What it didn't want the public to know ... well, that the public had to figure out for itself. What the Legislature was not so forthright about was, of all things, its effort to thwart the public's right to know what the Legislature and its members do from day to day.

In the middle of Sunshine Week, an annual occasion to call attention to the need for transparency in government, the Assembly was quite eager to tout various pieces of legislation: a bill to limit the state's ability to withhold public information on the grounds that it is copyrighted. A bill to end the practice of law enforcement agencies denying records simply because they're connected to an investigation, and to allow judges, not police, to decide whether information in a judicial proceeding should be withheld. Another to require greater disclosure of state property leases. And another to require disclosure of the identity of political action committees that fund those often-anonymous political mailings. All commendable. But while lawmakers were telling state agencies, police, courts, and PACs to be more transparent, they were also trying to ensure that one entity didn't have to be more open: the Legislature itself.

In their one-house budgets issued this week, the Senate and Assembly stripped a proposal by Gov. Andrew Cuomo to make the Legislature subject to the state's Freedom of Information Law. The governor had included the measure in his executive budget. Disappointing as this is, it's hardly a surprise. The Legislature has always resisted the idea of having lawmakers live by the same rules as the rest of government. So while the governor's calendar, phone records and emails are subject to FOIL, the powerful Senate majority leader's and Assembly speaker's are not. Nor are those of other legislators. While letters to the governor fall under FOIL, too, correspondence to legislative leaders and other lawmakers does not. The running excuse for this secrecy for more than four decades since FOIL was created has been to protect the privacy of communications between legislators and constituents — as though a letter from a citizen or a business to a lawmaker is somehow more sensitive than a letter to the governor. Why? Beats us. Lawmakers have probably come to assume New Yorkers just accept this opacity as the norm, but it's not in some other states. State legislators in Washington have tried for two years to make more of their communications secret, only to face an uproar from press groups, and, more importantly, from ordinary citizens who know that freedom of information and open meetings aren't some abstract privileges for journalists, but things that make government accountable to the people.

That should apply to all of government, including the Legislature that spends the taxes we all have to pay and writes the laws we all have to obey. |

Editorial Board Adirondack Daily Enterprise, Saranac Lake

|

A transparency backslide continueLast September, we editorialized about a practice that was growing in New York state government, in which official spokespeople for agencies won’t let us quote them by name. Instead, they insist that their remarks are “on background,” which is journalism jargon meaning we can use their quotes but cannot attribute them to that person by name. Instead, they say we can attribute the statements to the agency as a whole or with some vague description such as “officials say …” Where’s the accountability in that? And why our state government backsliding on transparency in this way, of all ways? We revisit the topic now because this is Sunshine Week, an annual occasion for calling special attention to laws and standards of open government. We are sad to report that the situation has not gotten any better in the last six months. The agencies that do this haven’t stopped, including the Department of Environmental Conservation, Department of Corrections and Community Supervision, and the Office for People With Developmental Disabilities. On the upside, the practice doesn’t seem to have spread to other agencies we deal with regularly. We haven’t yet heard this guff from spokespeople for the New York State Police, Department of Transportation, North Country Community College or the Adirondack Park Agency. We hope we never do. We are not sure why the practice is inconsistent, and we are not certain who is ordering it. It seems like it’s coming from the top down and that the spokespeople are following orders, but they haven’t explicitly said that. We think it’s important to let you, our readers, know that this practice is unacceptable to us. When a government spokesperson says an official statement is “on background,” our reporters are required to tell that person they cannot accept that. Such statements are either not reportable, as if they were off the record, or we must apply our protocols for anonymous sources, which require speakers to credibly explain how harm could come to them if we reveal their names — also, the statement must be so important for the public to know that we are willing to stick our necks out to publish it. It isn’t fair to you, the reader, if we let these public-relations people call the shots and expand our grounds for quoting anonymous sources, without giving reasons. You pay money for this newspaper and deserve credible answers, which includes knowing where news is coming from. More and more, Americans are skeptical of the news media — and we’re OK with that. Some of the doubts are due to a national political smear campaign, but we welcome fair-minded scrutiny. Reporters and editors should be accountable for where and how they gather information, and how they convey it to the public. The goal is to share “the best obtainable version of the truth,” to quote Watergate reporter Carl Bernstein, in a trustworthy manner so everyone can understand the reality we face. Journalism is far from an exact science, but there are some practices that are better than others. Some of those are as simple as covering your own butt. For instance, it’s important for us to show our sources so people don’t falsely accuse us of making things up. Yes, there is an important place in journalism for anonymous sources. We avoid using them whenever possible, but we all know that institutional powers sometimes don’t want to reveal things to the public that the public wants and needs to know. Sometimes people inside those institutions, who know what’s going on, are on the side of the public’s right to know and are willing to tell them the truth via the media. To keep them from getting fired, or worse, we agree to use them as anonymous sources. But a official government agency spokesperson is not a whistleblower when he or she gives a public statement on the agency’s behalf. That is not a leak; it is official government communication. This was always understood until now. Neither we nor the public has been given a reason for why it is changing. How pathetic is it that this Sunshine Week, instead of being able to report slow but steady progress toward a more transparent democracy, we have to talk about a trend in the opposite direction — in which even the professional mouthpieces of government agencies act as if what they have to say is shameful and they can’t have their names attached to it? Again, we are not sure who is ordering this practice, but we know Gov. Andrew Cuomo has the power to stop it, whether he started it or not. Again, we urge him to do so. This is one more of those little things that breeds distrust in government, and Sunshine Week is an appropriate time to shine a light on it. |

Please note: Previous Sunshine Week content is still availabl

Last September, we editorialized about a practice that was growing in New York state government, in which official spokespeople for agencies won’t let us quote them by name.

Instead, they insist that their remarks are “on background,” which is journalism jargon meaning we can use their quotes but cannot attribute them to that person by name. Instead, they say we can attribute the statements to the agency as a whole or with some vague description such as “officials say …”

e for download and use.

Click here to access the eight newspaper in education features created for 2012 (3 column x 8 inches) - an overview of NYS FOIL, Open Meetings, How to gain access to records and one freature on Freedom of Information and NYS Courts.

Click here to access the five-part series of features highlights just a few of the websites with reports and other data that may be of interest to students and the general public. Graphic organizers to accompany these features are also available here as PDF download. The topics included:

• What is “E-Government”? – A brief summary of our “Cyber Sunshine” focus

• Vehicle Safety – Highway Safety Data

• Food Safety – Restaurant Inspection Reports

• School Safety – Violence and Disruptive Incident Report

Finally, click here to access five public service announcements in PDF format (2 columns x 6 inches) that can be use to promote Sunshine Week

If you'd like to make a donation to the NYNPA Newspaper In Education program, simply press the Donation button below.

Your generous gift will be processed through the New York Newspapers Foundation's secure PayPal account.

New York News Publishers Association, Inc.

Phone/Fax (518) 449-1667 - Toll-free: (800) 777-1667